Linux kernel and vulnerabilities

The posts thus far have focused on mitigating or reducing the impact of potential exploits in user space code. Successful attacks against such code can be disastrous, however the impact might be reduced if various security measures are taken in the system. For example, processes should run at reduced privileges, code which interfaces with external data should distrust that data, etc.

Attacks which involve exploiting vulnerabilities in the kernel may be worse, however. Not only do Linux kernel vulnerabilities tend to be long lived [source, source], but some may result in total system compromise. Consider a recently discovered vulnerability discovered affecting bluetooth devices, named BlueBorne. This vulnerability allows an attacker who is able to initiate a bluetooth connection to remotely execute arbitrary code with kernel privileges. The vulnerability is a stack overflow issue due to how the kernel processed certain configuration responses from a remote client.

Although this vulnerability has existed unpatched from 2012 through 2017, it turns out that there was a mitigation available since 2014 to reduce its impact to a denial of service attack: kernel stack smashing protection [source]. This works in the same way that stack smashing protection operates in user space, in that GCC can compile the kernel with -fstack-protector or -fstack-protector-strong. For more details on these flag, see the post on stack smashing protection.

This post focuses on kernel stack smashing protection and its performance impact.

Analyzing stack smashing protection in the Linux kernel

As -fstack-protector-strong strikes a balance between security and performance, this version of SSP is analyzed when enabled when compiling the Linux kernel. Two metrics relevant to an embedded system will be used for the analysis:

- Increased code size for the kernel

- Performance cost

To facilitate the analysis, a custom Linux distribution was built using Yocto, one build with SSP enabled in the kernel and one without. The build was run on QEMU and analyzed. See this post on how to create a custom QEMU image, in my case on macOS.

The Yocto build was a bare-bones build with one exception: FFmpeg was included which will be used to compare performance. Adding FFmpeg was accomplished by adding the following to the conf/local.conf file in the build directory:

# Add ffmpeg and allow its commercial license flag

CORE_IMAGE_EXTRA_INSTALL += "ffmpeg"

LICENSE_FLAGS_WHITELIST += "commercial"

# Add extra space (in KB) to the file system, so that the

# benchmark has space to output its file(s).

IMAGE_ROOTFS_EXTRA_SPACE = "512000"To enable SSP the following kernel configuration was added:

CONFIG_CC_STACKPROTECTOR_STRONG=yCode size

The kernel images being compared are the bzImage files created by Yocto. Following are the sizes in KB of the kernel images from the two builds:

| Build | Size (KB) |

|---|---|

| No Flags | 6,881 |

| SSP | 6,994 |

This shows that SSP code instrumentation adds an additional 113 KB. This is an increase of ~1.6%. Although the percentage may be fairly high, the actual size difference is relatively small.

Performance cost

Adding the additional instructions for checking the stack in some functions will result in some performance cost, as the additional instruction do take time to execute. However, the question is can the performance cost be measured or is it exceedingly small?

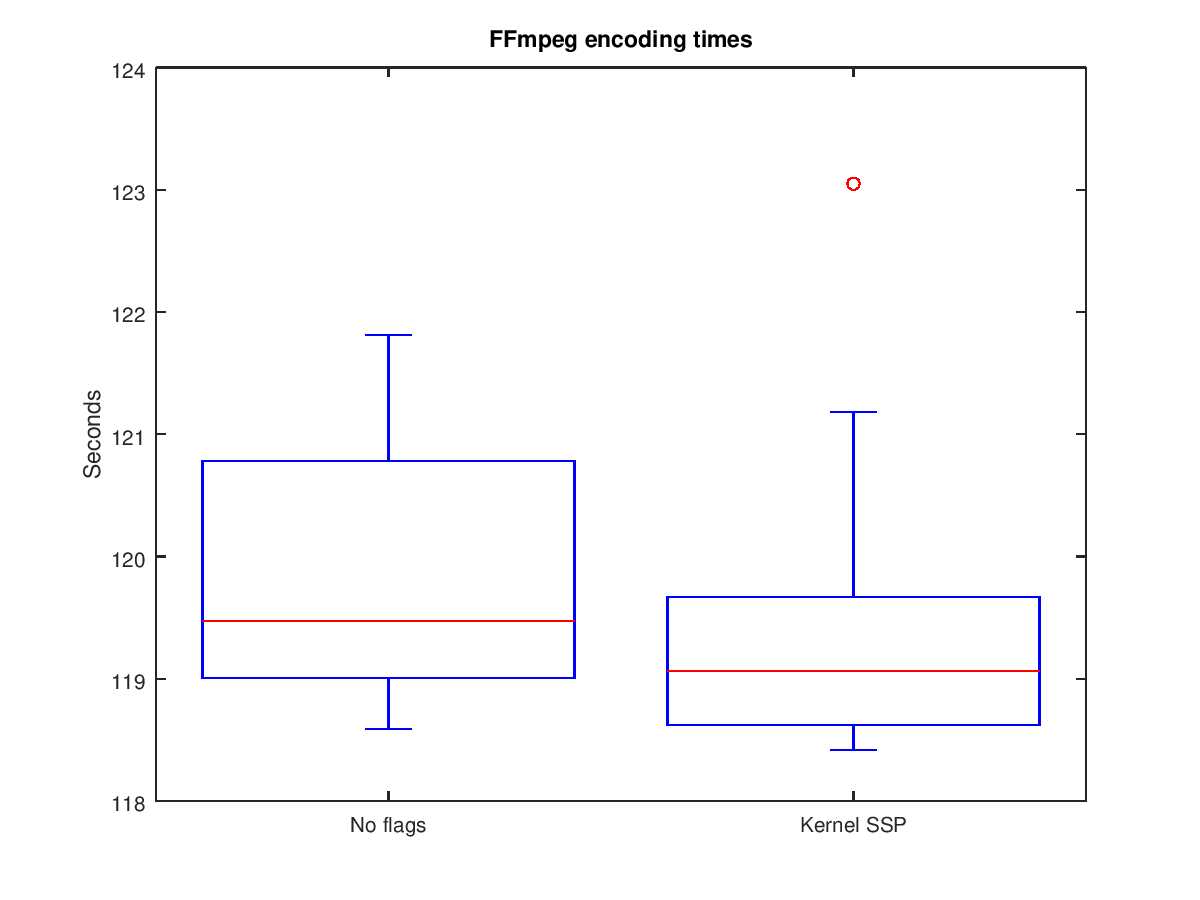

To quantify the performance impact, an experiment was conducted which encoded a small video 20 times in succession using FFmpeg, once with and once without SSP. See this post for details on the experiment and the video file which was used.

The following two box plots show the results of the experiment (raw data here).

The results do not conclusively show that compiling with SSP results in noticeable performance loss. The data implies that enabling SSP may slightly improve performance, but this expected to be an artifact of a reduced number of trials. Instead, it appears that the performance impact of enabling SSP in the kernel is minimal.

Conclusion

Stack Smashing Protection does provide some protection against latent buffer overflow defects which could be exploitable. Enabling it in the kernel did increase the size of the kernel (113 KB in this case), but no meaningful performance hit could be detected. As exploitable kernel bugs can be long lived, and the impact in enabling SSP is low but its ability to reduce the impact of exploits has been demonstrated, it should be worth enabling it on all but the most resource constrained systems.